Contextualized Learning

You want to teach in the best way to enable the learners to use and retain the information and skills. How can you do this if the learners can’t see the relevance? Contextual learning can help you address these concerns.

Often, literacy learners have trouble understanding academic concepts (such as math concepts) when they are taught in the abstract or taught separately. Even though the learners know they will need these skills as they move to their goals of employment, further education or independence, they struggle to make the connections to using them outside the classroom.

“relating instructional content to the specific contexts of learners’ lives and interests increases motivation to learn”

Dirkx and Prenger, 1997

However, learner interest and achievement improve significantly when they can put learning into their own frame of reference. They need help to make connections between

- new knowledge and experiences they have had

- new skills with skills they have already mastered

- the concepts they are learning and practical applications for using those concepts in the real world

Some examples of contextualized learning are:

- Learners identify forms that they need help understanding or completing, such as, bills, leases, tax forms and work documents.

- Practising job search skills, such as, viewing job postings and determining what would be needed to apply, creating a resume, etc.

- Using a piece of equipment safely, i.e., a photocopier for work, a sander or drill for home or work, etc.

- Attending a talk on tenant rights and responsibilities.

- Learning study and test-taking skills to prepare for further schooling. Examples might be taking sample GED tests, employment tests or mature student college entrance tests.

You might be interested in viewing the report done in 2018 by Community Literacy of Ontario, HANDS ON, SKILLS UP! Employment-Related Experiential Learning in Literacy and Basic Skills Research Report. This resource may be found in the Resources & Webinars, Newsletters section of CLO’s website

Some programs are running workshops specific to contextualized learning. Some examples are cooking, writing fiction, creating crafts, simple carpentry, working with digital pictures to make gifts, getting your G1 licence, etc. All these workshops are based on a platform or in the context of a “special interest” to the group of learners, but they are learning OALCF-based competencies/task group tasks, as well.

It’s Not Skills vs. Tasks, It’s Both

“The OALCF:

- supports the development of task-based programming

- helps practitioners focus on strengthening the learner’s ability to integrate skills, knowledge and behaviours to perform authentic, goal related tasks”

from OALCF Overview

The above quotation shows that LBS learning within the Curriculum Framework is task-based, but it also includes the integration of skills, knowledge and behaviours. An exploration of four aspects of literacy learning takes place in OALCF Foundations of Assessment and the OALCF Selected Assessment Tools (also see Literacy Basics Assessment Module, Assessing Different Aspects of Literacy to Determine Goal Completion). The four aspects of literacy learning are:

- Skills Development

- Skills are discrete descriptors of literacy and numeracy development, such as decoding, recognizing sentence structure, and locating information.

- Task Performance

- Tasks emphasize more than skills, as they consider purpose, context and culture to reflect actual use.

- Social Practice

- Understanding literacy and numeracy as a social practice involves consideration of what people are doing, feeling and thinking when they are engaged with actual print and numeracy activities.

- Change

- People respond to change and make changes in their lives and the lives of others when they participate in a literacy program.

LBS learning helps learners

- acquire skills to be used to complete tasks

- complete tasks

- put the skills and task completion ability into everyday practice

- respond to change and make changes in their lives and in the lives of others

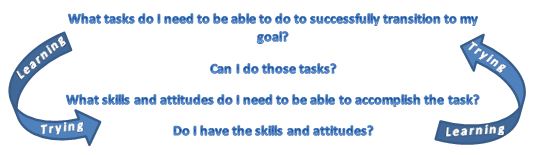

But do you teach the skills or the tasks first? It is somewhat like the chicken and the egg dilemma. The learners need the skills to complete the tasks, but they also need to understand

the task and know they can’t complete it, before they will see the value in learning the skill. So, it is often a back and forth activity.

Because a learner has the ability to do skill “x” does not mean the learner is able to use that skill in completing a task. Competency or skill-based training may give the learner all of the individual skills such as reading, writing or math, but it does not effectively integrate these skills into a whole task that may be required in the real world.

Task-based learning, on the other hand, allows the learner to see from the beginning where each piece of the puzzle fits into the overall picture. It allows the learner to fully integrate each skill into the performance of the task.

In task-based instruction you start by looking at the whole task and then breaking it down into a series of smaller and smaller tasks. You then work your way down until you get to the mini-tasks, the performance/task desriptors and skills that work together and build on each other. Each mini-task is introduced separately and the learner masters the skill(s) involved for that task. As new mini-tasks are added, the learner practises the previously learned skills as part of a bigger picture. The learner continually works toward mastering each skill while getting a sense of how that skill fits into the larger task and life/goal situations. This is called a scaffolding approach.

This approach allows you to concentrate on presenting and developing the new skill sets while allowing for the repetition of previous skills as part of the process. You provide more assistance as you introduce new or difficult tasks. While the learner masters the skill/task, you gradually decrease your support and shift the responsibility for learning to the learner.

Developing Goal-Directed, Task-Based Learning Activities

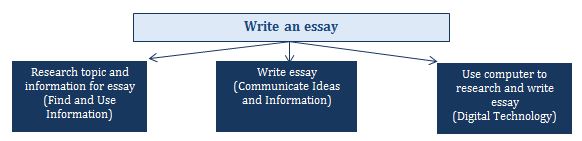

Let’s start with the tasks rather than the skills. Say you have a learner with a secondary school credit goal. One task the learner may need to accomplish is writing an essay. This task includes smaller tasks that require three different competencies.

We’ll look at the Communicate Ideas and Information competency in more detail. The skills involved in the task group Write Continuous Text are

- Mechanics – punctuation, spelling and grammar

- Style – voice, vocabulary, formality and sentence structure

- Organization – sequencing, order

- Visual Presentation – structure, legibility

- Purpose and Form – writing for various purposes

Example tasks the learner could work on that would be relative to their secondary school credit goal path and that could be used to practise or demonstrate the skills are:

- Write a short note to your instructor to explain the topic for your essay (Level 2)

- Write an email or a post to a wiki or blog to explain to others how you sequence and organize paragraphs in an essay (Level 3)

As the learner tries the various tasks, you assist them with any parts of the task they have difficulty with. You provide instructional support with skills, as necessary. When the learner is ready you suggest increasingly more difficult tasks that allow the learner to build on their success.

The important thing to remember is that you don’t teach skills in isolation. To be motivated, adult learners need to understand how the skills will be used to complete tasks necessary to their goals. They also need to apply their skills to perform authentic or real-life tasks that are appropriate to their lives and to their goals.